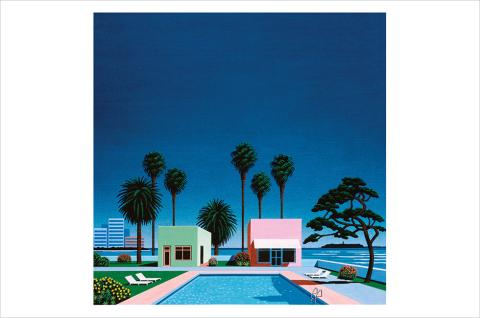

Pacific Breeze: Japanese City Pop, AOR & Boogie 1976-1986

One of the most surprising nominees for the 2020 Grammy Awards came in the category of Best Historical Album. While the category is usually filled with reissues of classic American blues, rock, and jazz, this year, there was an offbeat choice from the small independent record label Light in the Attic: the album “Kankyo Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990”. The compilation features minimalist, lulling soundscapes by Japanese musicians, some well-known (Joe Hisaishi, Yellow Magic Orchestra) but others unfamiliar outside of Japan. Though it ultimately didn’t take home the golden gramophone, this niche album’s nomination demonstrated a trend that has finally broken through into the mainstream: the ongoing revival of vintage Japanese music by global music fans, thanks to the magic of the Internet.

Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990

While obsessive music fans have always enjoyed excavating unknown tunes from far-away places and/or from eras past, there has recently been a surge of interest in Japanese music culture from the 1960s-90s, facilitated by YouTube and other online communities. There has long been an international fandom for contemporary J-Pop, widely available today through digital streaming services and for purchase. But music from before the digital revolution has been far more difficult to access, and used to require dedicated sleuths scouring the dusty record shop bins for rare vinyl or cassettes, and buying, selling, or trading these precious artifacts as part of an expensive hobby.

Of course, the Internet changed all that. Record hounds began uploading their finds to digital platforms for a broad audience to discover, driving curiosity about these genres and creating new fan-bases for artists from long ago (some of whom are no longer alive). Soon enough, small Western record labels began licensing some albums for official reissues, as well as original Japanese record companies deciding to re-release materials from their vast archives to capitalize on the trend.

The 1980s were a particularly fertile time in the Japanese music industry due to a growing consumer class with an appetite for new releases, and new formats for distribution like cassette, Laserdisc, and CD, as developed by the nation’s electronics companies like Sony, Casio, Toshiba, and Panasonic.

Pacific Breeze 2: Japanese City Pop, AOR & Boogie 1972-1986

One of the prominent genres that flourished because of this was City Pop, a blend of international disco, funk and R&B with Japanese vocals and an upscale, urbane feel. City Pop has had perhaps the most prominent renaissance online, with thousands of hours of videos uploaded by fans to YouTube, a bustling community on the Reddit discussion board, and even “City Pop”-themed DJ nights at dance clubs and bars around the world. The music and its album covers deliver a fantasy of cosmopolitan life in 1980s Japan – with its cutting-edge fashion, cars, electronics – and many younger fans of the music describe its appeal as triggering nostalgia for a time they never knew. Key artists who have won new fans from their association with City Pop include Mariya Takeuchi, Tatsuro Yamashita, Anri, Momoko Kikuchi, and the genre-bending legend Haruomi Hosono (earlier, a founder of Happy End and Yellow Magic Orchestra). Last year the same record label behind “Kankyo Ongaku,” the Seattle-and-Los-Angeles-based Light in the Attic released the “Pacific Breeze” compilation as an introduction to City Pop – the sequel, “Pacific Breeze 2,” will debut in May on vinyl and is already available on some streaming services.

Jun Fukamachi | Courtesy of the Jun Fukamachi Project

For those who go down the City Pop rabbit-hole, they might stumble onto more experimental works – the free jazz, psychedelic rock, and prog rock that pushed the boundaries of the mainstream from the 1970s on. Obscure, challenging albums from musicians like Osamu Kitajima, Yuji Ohno, Akiko Yano, and Jun Fukamachi have gained large followings on YouTube for their bold forays into cosmic jazz, electronic noise, and surreal vocal stylings. Here again is territory where the prolific Haruomi Hosono made his mark. After getting his start in the folk-rock outfit Happy End, Hosono co-founded Yellow Magic Orchestra with Ryuichi Sakamoto, then branched out on his own to create both slick City Pop-ready tunes, and shockingly eclectic albums like “Cochin Moon”, “Paraiso”, and “Hosono House” that incorporated everything from Bollywood influences to the sounds of bubbling water, squawking birds, and metallic zippers. His recent popularity via streaming platforms and reissues (also by Light in the Attic) led to a sold-out tour across America in summer 2019.

Hosono was also a pioneer in ambient music and was even commissioned by the retail brand Muji to create background music for their stores in 1984. This 15-minute looping track, composed of soft synthesizer tones with occasional music-box-tinkling accents, is included on 2019’s Grammy-nominated “Kankyo Ongaku” compilation, and reflects the delicate 1980s minimalism that has also become wildly popular on YouTube. Other essential artists include Satoshi Ashikawa, Fumio Miyashita, and Hiroshi Yoshimura, whose works engage with the international history of minimalist and mood music, but with a distinctly Japanese twist. Yoshimura was known for his “environment music” that took inspiration from nature as a counterpoint to the hyper-urban acceleration of the 80s and 90s in Japan. His albums like “Soundscape I” (1986), “Flora” (1987) and “Wet Land” (1993), evoke a slower pace of life near forests, rivers, meadows, and seashores. Though Yoshimura passed away in 2003 before YouTube even existed, the platform gave his work a second life, particularly through its mysterious algorithm that began recommending tracks to users seeking some relaxing sounds – which is to say, millions of people around the world. The label Light in the Attic just announced that they will be reissuing “Green” (1986), Yoshimura’s long out-of-print masterpiece of water sounds and floating tones, as part of a new imprint called WATER COPY in collaboration with the late musician’s estate focusing specifically on his works.

There’s perhaps never been a better moment to discover, or rediscover, vintage Japanese music through this digital revival. From the nostalgic escape of City Pop, to the mind-expanding jams of free jazz, to the calming effects of ambient– global listeners can each find their own soundtracks for these challenging times.