What makes a business successful? In some cultures, some common answers might be exponential profits or worldwide expansion. In Japan, however, there’s another key metric of success: longevity. Japan is home to the world’s oldest companies; according to Research Institute for the Centennial Management, over 52,000 companies in Japan are at least a century old, many with histories spanning multiple centuries. Known as shinise (which translates literally to “old shop”), these firms have weathered natural disasters, wars, pandemics and more, guided by certain values and by a careful balancing of tradition and innovation.

Long a point of national pride, Japan’s shinise are now becoming a source of global inspiration, with many international publications profiling these historical businesses with curiosity and admiration (such as a New York Times profile on the thousand-year-old Kyoto shop, Ichimonjiya Wasuke). In June 2021, JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles launched a webinar series exploring the secrets to such long-term business sustainability; the second webinar is scheduled for September 2021. (Click here for the event page.) What has enabled the shinise to not just survive, but thrive, over such long time periods and through countless upheavals? And what can businesses around the world learn at a time when sustainability is more critical than ever?

It’s true that long-lasting companies can be found in other countries — Germany, for instance, has some breweries and wineries that date back to the 11th century — but as shown in a study done by the Bank of Korea in 2008 surveying 41 countries, over 56% of companies older than 200 years are in Japan. The type of companies that reach shinise status range across several categories, but most trade in goods that are central to daily life (like food and beverage), traditional crafts or kogei (like metal and papercraft), or objects with deep cultural resonance (such as religious goods). A few, however, may be surprising — such as Nintendo. Today known for its videogames like Super Mario Brothers and the multimedia empire Pokémon, the company began in 1889 in Kyoto making playing cards. Like Nintendo, another shinise that expanded far beyond its humble origins is Kikkoman, the soy sauce manufacturer that was officially founded in 1917 but whose founders had already been producing soy sauce for 300 years. While these examples are now large global companies, the majority of shinise are family-owned and have stayed smaller in size — and even Kikkoman’s Executive Corporate Officer Osamu Mogi (a special guest in the inaugural webinar) is a descendent of one of the eight founding families of the company. A webinar held in September 2021 featured the CEO of Yamamotoyama U.S.A., a respected tea company that has operated a shop in the same location in Tokyo for more than 330 years. Though it has expanded its operations overseas, it remains family-owned. (Watch video here.)

Keeping a business in the family allows shinise to pass down other key values from generation to generation. In some instances, family firms have even adopted heirs to ensure there will be a next generation to run things. But a company must have a strong foundation in the first place to create a legacy worth passing on.

The foundations of shinise are forged through perspectives and practices that differ from the focus on growth found in many contemporary global companies. One bedrock principle is wanting to protect the brand’s good name — so gaining and keeping the trust and loyalty of customers is paramount. This impulse also leads to slower and more incremental change, and to deprioritizing short-term profits in favor of long-term sustainability. For instance, a hundred-year-old tea shop might decide against a potentially profitable practice of also offering cakes if this action would risk impacting the quality and consistency of their customer service and alienating their most loyal tea customers.

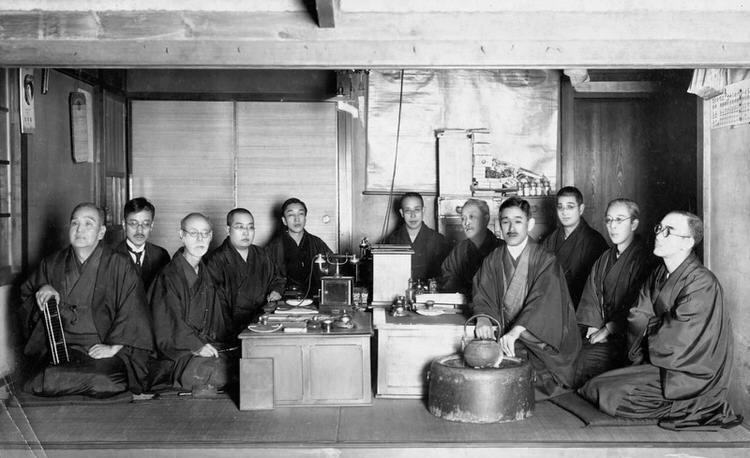

Courtesy of Kikkoman U.S.A.

As well as considering the wishes of their customers, shinise also try to carefully balance their connection to their competitors, and their industry at large. As shared in the first Business Longevity webinar, Kikkoman’s ECO Mr. Mogi described how during World War II, there was a shortage of soy beans and other raw materials that led other soy sauce producers to experiment with “chemical” additives in their product. Kikkoman had invented a new method to continue traditional fermentation in a more efficient way — but instead of guarding this secret and taking 100% of the market share, they released this technique to their competitors to stabilize the soy sauce industry (and prevent a feared “race to the bottom” of poor quality). Their vision was much larger than their own company; it was to ensure the quality of an essential household staple, and to understand their own place in the fabric of Japanese society.

Throughout the history of shinise, we see examples of how the company’s good name, relationship with their community, and ability to survive even on small profit margins with little or no annual growth, are seen as more important than revenue growth or market expansion. These companies provide a contrast to many contemporary corporations which are often balancing the needs of investors to grow their investments and the hope of going public with an IPO. While shinise see themselves in an interconnected web with their founders, employees, customers, neighborhoods, raw materials of their products and the environment itself, many “young” companies around the world are not as focused on these concerns. However, especially at a time of climate crisis and the inequalities laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more entrepreneurs are starting to look to the example of shinise which demonstrate healthy, sustainable ways to do business for good.

They can also take a final inspiration from the fact that products made by shinise are serve as status symbols — the strongest “branding” one could ask for. They are perhaps the ultimate luxury goods. While time is something money can’t buy, you can purchase a perfectly-crafted mochi from a thousand-year-old sweetshop like Kyoto’s Ichiwa — and it tastes delicious.

Related Programs

Session 1 | Kikkoman U.S.A.

An Introduction to Centuries-Old Businesses in Japan

Photo provided by Kikkoman Corporation

Session 2 | Yamamotoyama

Looking into the Future with the Next Leader

Courtesy of Yamamotoyama