When legendary director Michael Mann announced in 2020 that he was filming an entire television series for HBO in Japan, with a bi-cultural cast largely speaking Japanese, it was considered ambitious – and risky. Today, the success of “Tokyo Vice,” now in its second season, could be considered just the first illustration of an exciting, brand-new era in Japan-Hollywood collaborations and crossovers across film, TV, and other entertainment. It has also been a noteworthy moment for increased distribution, visibility, and fandom for Japanese domestic productions on the world stage. What is making this such a dynamic time for film entertainment within Japan and collaborations abroad?

In the first quarter of 2024 alone, American audiences have been treated to the premieres of the second season of “Tokyo Vice,” FX Networks’ historical epic “Shōgun,” and Apple TV’s Colin Farrell-starring “Sugar” (the first episode of which takes place partly in Japan). In the realm of feature films, there have been Oscar wins for the international smash hit “Godzilla Minus One” (directed by Takashi Yamazaki), and anime legend Hayao Miyazaki’s first film in 10 years, “The Boy and the Heron,” as well as a nomination for arthouse favorite “Perfect Days” (directed by German director Wim Wenders, starring one of Japan’s beloved actors, Koji Yakusho).

*To watch the video in full screen, please click play and then the YouTube icon on the lower right-hand corner.

The history of Japanese cinema began in the late 1800s, around the same time as filmmaking in America and Europe and developed on its own timeline through the upheavals of WWII. Some Japanese films, such as the works of master Kenji Mizoguchi, even screened in the U.S. in the 1930s, but international distribution was limited. In the postwar period, the first film to gain wide release in the U.S. and be classified as a semi-coproduction was Toho Studios’ iconic “Godzilla” (1954). The film was dubbed into English, re-edited, had scenes added with American actor Raymond Burr, and was renamed “Godzilla, King of the Monsters!” (1956). It was a commercial success and served to introduce Godzilla to the world. As the Japanese film industry strengthened in the postwar period, international films and TV were filmed on location in Japan and partnered with local crews and producers. These included the 1965 film “None but the Brave” starring Frank Sinatra, the 1967 James Bond film “You Only Live Twice,” and most notably, the original 1980 mini-series of “Shōgun” starring Richard Chamberlain, the first U.S. television series to be filmed entirely in Japan.

©2009 Yaro Abe, Shogakukan Inc./Shinyashokudo Production Committee

In the decades since, diverse Japanese films and TV have gained success in international distribution overseas, ranging from arthouse fare, to action cinema and anime features and series. Notable crossovers and co-productions took place in Europe with countries like France that have more robust cinema funding for less commercial works. And in 2003, a trio of American films filmed entirely or in part in Japan – “Kill Bill,” “Lost in Translation,” and “The Last Samurai” – were released to great acclaim. But beyond theatrical cinema, it was the rise of digital streaming television that dramatically changed the eco-system. As streaming platforms like Netflix licensed and subtitled domestically produced Japanese TV series like “Terrace House” and “Midnight Diner,” they became hits overseas, demonstrating that there was a much larger English-speaking audience hungry for Japanese content. This helped pave the way for other cross-cultural collaborations and enabled Hollywood filmmakers to consider filming on location in Japan, something previously considered complex and expensive.

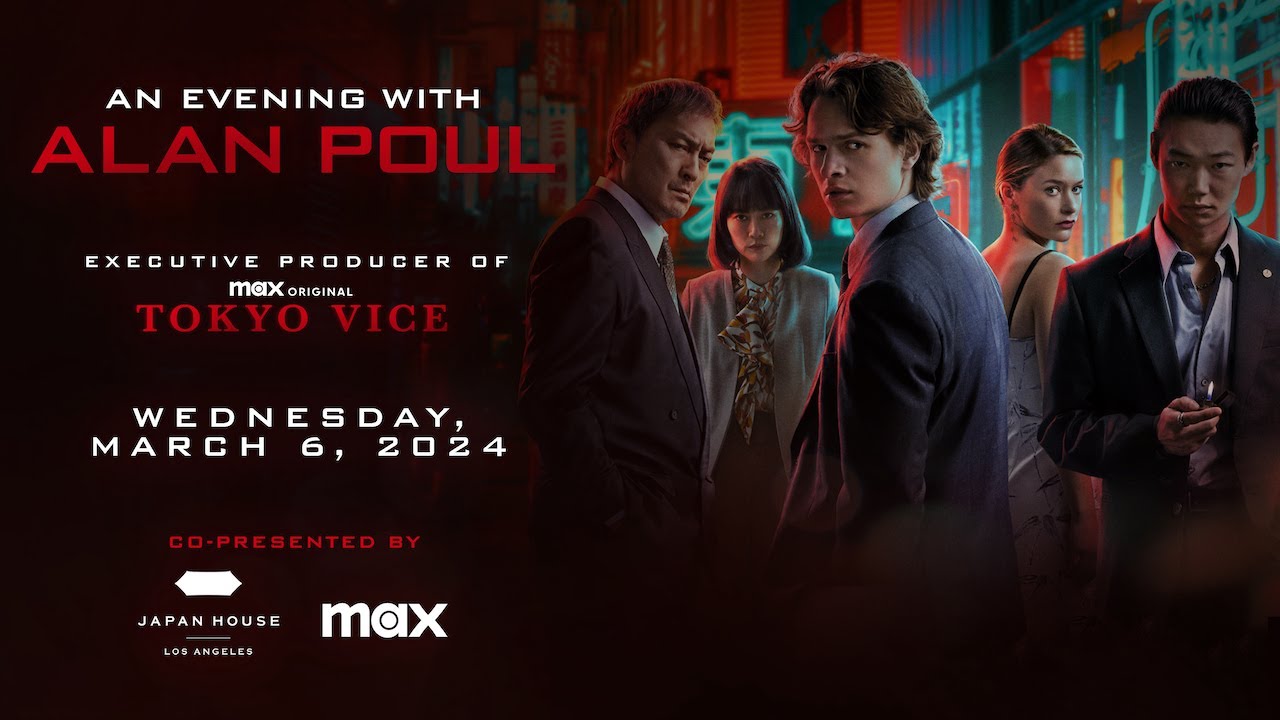

Even in this new era, foreign productions still face various challenges to filming on location in Japan, including high costs, complications involved in obtaining proper permits, managing a multi-lingual crew, and navigating Japanese culture respectfully. But, increasingly, international filmmakers are finding these challenges outweighed by the unique landscape, local film talent (in front of and behind the camera), and the creative innovation and inspiration found there. JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles has twice hosted the filmmaking teams behind “Tokyo Vice” for exclusive talk events – director Michael Mann in 2021, and executive producer and director Alan Poul in 2024 – both of whom spoke about the distinctive benefits of filming in Japan and expressed their hopes that improving the financial incentive system (like tax credits given by the film commissions in other countries) could attract and facilitate even more international productions. (Watch the full conversations online, with Michael Mann, as well as Alan Poul).

© JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles

Following the critical and commercial success of “Godzilla Minus One,” stories abounded in the foreign press about the extraordinary creative vision that was pulled off with a relatively small budget – highlighting not just the talents of director, screenwriter, and VFX visionary Takashi Yamazaki, but his phenomenal team. At an event at JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles, Yamazaki described the unique workflow of Japanese visual effects productions, and how he achieved miraculous outcomes with limited time and resources (watch the program here). After “Godzilla Minus One” became the first Asian film to win an Oscar for best visual effects, industry pundits have been predicting more interest by foreign productions to tap into the groundbreaking skills of Japanese VFX artists and crews. In recent months, FX Network’s “Shōgun” has been compared to “Game of Thrones” as a true TV epic. Although it is only one season long, the series presages other potential projects from its creative team, which forged a truly cross-cultural production, from language to food to historical accuracy (JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles also hosted an exclusive premiere event with starring actor and producer, Hiroyuki Sanada).

Around the world, the creative industries and film in particular face reduced funding and rapidly transforming business models. In this uncertain time, the surge of energy around Japan-Hollywood collaborations and Japanese entertainment in general can light the way to even more sustainable cross-cultural productions in the future.

Photograph by James Lisle Max

Photograph by James Lisle Max Courtesy of FX Networks

Courtesy of FX Networks Courtesy of Animation is Film

Courtesy of Animation is Film Courtesy of NEON

Courtesy of NEON