One of Japan’s most beloved folktales is “The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter” (also known as “The Tale of Princess Kaguya”), which centers on a magical baby found in the center of a bamboo stalk . The baby brings fortune to the bamboo-cutter and his wife who raise her as their own. While this ancient story takes many more twists and has supernatural dimensions, the basic premise reflects how bamboo is seen in Japanese culture: a vessel for almost miraculous bounty.

For millennia, the fast-growing, resource-efficient and versatile grass known as bamboo has been used in Japan for everything from handmade craft to cuisine – and has also become a symbol of strength, simplicity, and prosperity.

Perhaps one of the earliest purposes in Japanese culture was as food. Fresh bamboo shoots (takenoko) are the basis of many traditional dishes, prized for their nutritional value, subtle taste, and toothsome texture. Simmered, stir fried, in soups and stews, not to mention added to rice for a nutty flavor, young bamboo is a distinctive ingredient in Japanese cuisine. It has other roles in cooking as well, from the bamboo leaves used to wrap treats like the jellied bean-paste, youkan, or rice cakes, as well as bamboo skewers for yakitori and other grilled items, and utensils, strainers, steamers, baskets, and beyond. There’s even a summery tradition known as nagashi-somen or “flowing noodles”, in which a bite-sized bundle of cold noodles are sent flowing down a halved bamboo chute to be “caught” with one’s chopsticks and dipped into tasty sauce.

The iconic shape of young bamboo shoots is also the inspiration for a particularly beloved children’s candy: “Takenoko no sato”, comprised of cookie and chocolate, and found everywhere school kids have coins to spend on a treat. Bamboo is an ever-present motif across pop culture, fashion, and high art – from “Marby-chan”, the cartoonish bamboo-shoot-shaped mascot of Kurashiki City, to bamboo-leaf patterns commonly found on yukata and kimono, to traditional ink paintings (many of which would have been painted with calligraphy brushes made from bamboo). A key instrument in Japanese musical history is the shakuhachi flute, which originally entered Japan in the 8th century from China, but fell out of popularity and was reinvented in the 15th century, made from a single length of bamboo and associated with Zen Buddhist monks who used the flute as a part of their spiritual practice.

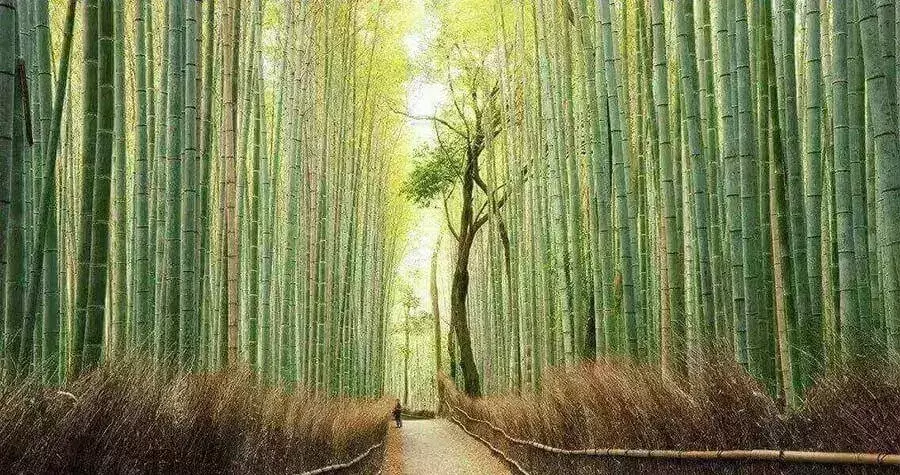

What a shakuhachi flute does on a small scale – creating a distinctive sound as air passes through the hollowed center of a bamboo stalk – an entire bamboo grove achieves on a far larger one. A breeze blowing through a forest of bamboo is an especially calming and transportive sound – wind rushing, leaves blowing, and bamboo gently knocking together. In Kyoto, one such grove, the Arashiyama Bamboo Forest, has been designated by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment as one of the “100 Soundscapes of Japan”, and attracts visitors from far and wide to immerse themselves in the unique sonic landscape (to sample this experience, put on your headphones and listen to the JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles’ ASMR video here). While the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing”, encourages people to use forested environments worldwide as a space for a mindfulness practice, a bamboo grove is obviously a special setting for contemplation and recharging.

Bamboo is often associated with spring, when new shoots emerge green though the earth, but it is also a principal element in traditional New Year’s celebrations in Japan. As part of O-shogatsu, families typically set up special decorations known as kadomatsu made of bamboo and pine; the bamboo connotes strength in the face of adversity, because of its quick straight grown and ability to bend without breaking in the strongest winds. Bamboo and pine are also two parts of the ancient grouping sho-chiku-bai, the “three friends of winter” (the third friend is plum) that symbolizes resilience and growth in tough circumstances, and gives its name to a popular sake brand launched by Takara Sake in 1933.

From a rustling grove to a shakuhachi flute, bamboo is exceptional growing in a group or as a single object, in its natural form or as a hand-made work of art, and demonstrates a fluidity across categories and its entire life span. With its many uses, bamboo is not just a star of cuisine, tradition, and sustainable design but serves as an enduring metaphor for collectivity, flexibility, and regeneration - qualities of value to us all.