In the popular imagination, the word ninja immediately conjures a dramatic image. We can all picture it – a mysterious figure emerging from the darkness, shrouded in all black and wielding exotic weapons, maybe even supernatural abilities too. Yet, like many cultural figures that traverse fact and fiction to become global icons, the true history of Japan’s shadow warriors is more nuanced – and even more fascinating.

The very term ninja itself is a relatively modern, alternate reading of the older term shinobi no mono (忍者) which can be translated as “a person of stealth.” (The character 忍 can be read “nin” or “shinobi” and means stealth and 者 is read “ja”or “mono” and means person). It is not clear exactly when the term ninja replaced shinobi as the common pronunciation of the name, but by the 20th century, Japanese writers of historical action novels were using it for these mysterious historical figures. In 1967, the word ninja entered the English language through the James Bond film “You Only Live Twice,” helping to popularize the use of this term internationally.

The emergence of the shinobi occurred within the complex political landscape of medieval Japan. As early as the 8th century, groups of outlaws had started forming their own rugged clans which were a far cry from the disciplined warriors of popular mythology. These groups eventually evolved into sophisticated networks of spies, assassins, bodyguards, and mercenaries during the tumultuous Sengoku Period (15th – 16th centuries), when Japan’s feudal lords recognized the value of clandestine warfare and intelligence gathering in their constant struggles for power.

The historical shinobi (and a female version called kunoichi) were highly pragmatic operators who prioritized survival and effectiveness over honor. Unlike the samurai who worked with noble classes in Japanese society, most shinobi came from lower-class farming families and worked for pay rather than out of loyalty. The famous Iga and Koga clans, far from being mystical warrior societies, were essentially regional families powerful enough to maintain their own militias. Their members were valued for being inconspicuous, expendable, and clever – qualities that allowed them to survive and thrive in Japan’s evolving medieval power structure.

Consider the career of Hattori Hanzo the First, whose life illustrates the reality of shinobi service. Rather than the supernatural warrior of modern fiction, Hanzo was a practical professional who left his home region to serve various lords, ultimately finding employment with Tokugawa Ieyasu, the military leader who eventually united Japan. His son, Hattori Hanzo the Second, later transitioned fully into the samurai class, establishing a clandestine institution under the Tokugawa Shogunate – an example of how shinobi adapted to changing political circumstances. As an interesting sidenote, because clans of shinobi were employed for pay, they did not have their own kamon or family crests, but when they worked under major feudal lords, they were associated with their employers’ kamon (to learn more about the history of family crests in Japan, read this article).

The tools and techniques of the historical ninja were equally practical. Rather than the iconic shuriken (ninja stars) of popular culture, they typically employed modified household items as weapons – nails, kitchen knives, and farming implements that wouldn’t attract attention during searches, but could still be lethal when wielded correctly. They were also skilled with herbal poisons to conduct assassinations with maximum secrecy. The straight-bladed swords, or ninjato, that they are said to have used were supposedly designed to be used with a precision thrust, not the more elegant motions of a longer-bladed sword like the curved katana. Some clans even developed sophisticated communication systems using colored rice seeds arranged in code – a very modest material repurposed for ingenuous subterfuge, and a marked contrast to the spectacular “smoke bombs” of fictional representations.

© Iga-ryu Ninja Museum

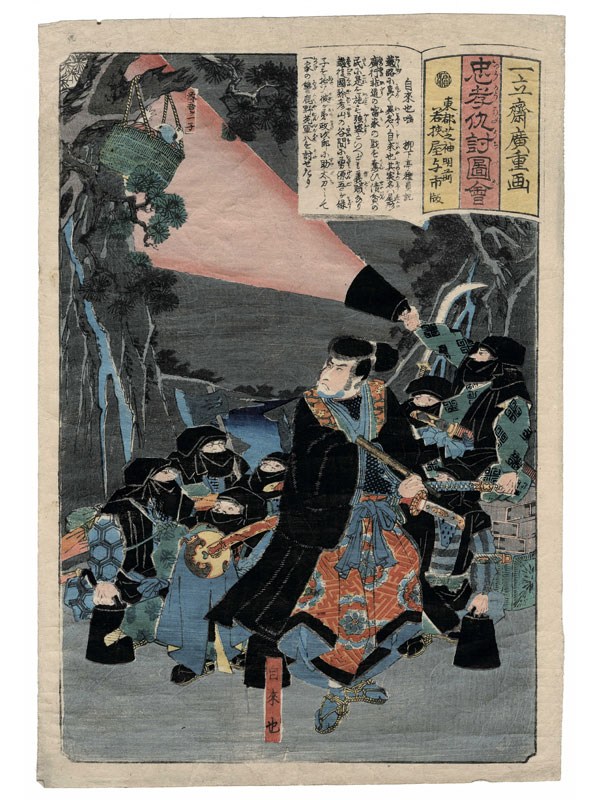

This transformation of ninja from historical figures to increasingly mythic characters began during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868). During this period, Japan’s unification created a more peaceful era and reduced the need for warriors in open battle. Some ninja were employed as bodyguards for military lords, but since the military government tightly controlled the populace in order to maintain a stable social structure and prevent uprisings, other shinobi shifted into more covert operations like espionage. And as their “active” roles diminished, their stories found new life in kabuki theater and popular literature, where their abilities grew increasingly fantastic. This theatrical reimagining would prove crucial to the ninja’s enduring cultural legacy, leading up to the modern mythology of ninja that fully took shape in the mid-20th century. The 1950s saw an explosion of ninja-themed historical novels in Japan that emphasized their superhuman abilities, and paved the way for what was referred to as a “Ninja Boom” in the 1960s as their reputation spread globally, coinciding with Japan’s post-war cultural renaissance. The 1967 James Bond film “You Only Live Twice” marked the ninja’s debut in mainstream Western cinema, beginning a cultural cross-pollination that would influence everything from Hollywood action films to manga series like “Naruto” to the zany 1980s media franchise “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.”

Today, the trajectory of the ninja serves as a prime example of how historical figures can be transformed by the cultural imagination. While scholars at institutions like Mie University’s Ninja Research Center study the historical reality of shinobi warfare, popular culture continues to reinvent the ninja for new generations. The last direct link to the historical tradition, Fujita Seiko – the 14th generation master of Koga Nindo who died in 1966 – bridged the gap between fact and fiction, teaching at a military espionage institute while witnessing his ancestors’ legacy reshape itself in the modern world. Today, visitors to Japan can indulge their ninja curiosity by visiting places like the Ninja Museum in Iga, that attempt to tell their true story (as well as riff on the popular mythology – to learn about Iga Prefecture’s connection to ninja history, read a recent article here).

The ninja’s transformation from medieval mercenary to globally recognized super-spy offers a compelling lens through which to examine how societies reimagine their histories. What began as practical wartime operatives – skilled in nimble survival rather than supernatural powers – has evolved into a potent symbol that transcends its Japanese origins. In this journey from shadow to spotlight, from historical fact to pop culture legend, the ninja embodies how cultural narratives can simultaneously preserve and transform their subjects. Perhaps most fascinating is how the ninja’s original virtues of adaptability and transformation have, ironically, enabled their story to survive and thrive across centuries and cultures, shape shifting to meet the imagination of each new generation.