Travelers visiting Japan for the first time often describe something notable about the way chefs, artisans, and even train conductors approach their work: a deep focus on details, and a dedication to craft itself. This visible sense of professional pride and dedication is hardly unique to Japan, but anthropologists connect it to a particularly Japanese concept known as ikigai, defined as a profound sense of purpose that transforms daily work into a reason for being. In recent years, books and workshops have helped introduce ikigai to the West, and academic researchers have explored how it may enhance physical and mental health. This ethos of finding deep meaning in the intersection of skill, service, and personal fulfillment has shaped Japanese society for generations, offering insights into how purpose can infuse every aspect of daily life.

Though only popularized in Japan in the 1960s, the term ikigai reflects a sophisticated understanding of life’s meaning that has evolved in Japan over centuries. The word combines “iki” (to live) and “gai” (worth or value), embodying the culture’s emphasis on harmonizing individual fulfillment with social contribution. Experts say that ikigai isn’t just about “finding happiness,” but about creating harmony between what you love, what you’re good at, and what your community needs. This philosophy reflects core Japanese values: the pursuit of wa (harmony), an unwavering dedication to mastery, and the understanding that personal excellence serves the greater good.

In traditional Japanese society, ikigai manifested through various roles that gave life its deeper meaning. Master artisans from carpenters to sword-makers found their ikigai in the patient perfection of their crafts, passing down techniques through generations while serving their communities’ needs. For the samurai class, ikigai was intrinsically linked to their code of honor and duty, while merchants discovered purpose in the honest conduct of business and service to society, and farmers discovered it in their vital connection to the land and its rhythms. Even within family structures, individuals found their ikigai in fulfilling familial duties and maintaining community bonds, demonstrating how personal purpose naturally flowed from one’s place in the social fabric.

The post-war transformation of Japan brought new interpretations of ikigai into focus. As skyscrapers rose where wooden houses once stood, corporate culture emerged as a novel arena where many Japanese sought their sense of purpose. Companies became more than workplaces – they became communities where employees could develop their skills, contribute to society, and find personal fulfillment. However, this era of rapid economic growth and competitive business brought new pressures and challenges to a changing society. In 1966, Japanese psychiatrist Mieko Kamiya addressed this yearning for purpose by publishing On the Meaning of Life, a handbook framing ikigai in modern terms and reviving its cultural relevance for a new era.

In the past decade, ikigai has become a global phenomenon. It’s perhaps no surprise that this Japanese understanding of purpose has struck a powerful chord with people worldwide seeking alternatives to metrics of success based solely on status, wealth, or consumption. The 2016 publication of Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life by Héctor García and Francesc Miralles was translated into over 60 languages and sold millions of copies worldwide, introducing ikigai’s principles to readers across cultures. In 2017, another influential text followed with The Little Book of Ikigai by Japanese neuroscientist Ken Mogi. Such texts have credited the concept not only with increasing happiness but also extending life expectancy. Recently, in response to the growing global attention to the concept, the Government of Japan devoted a web page to the concept here.

The international interest in ikigai has gone far beyond books and websites. Prominent companies like Procter & Gamble have begun incorporating ikigai-inspired principles into their employee development programs, recognizing its potential to enhance both workplace satisfaction and productivity. The concept has even found its way into higher education, with universities integrating ikigai frameworks into their career counseling programs to help students align their professional paths with deeper sources of meaning.

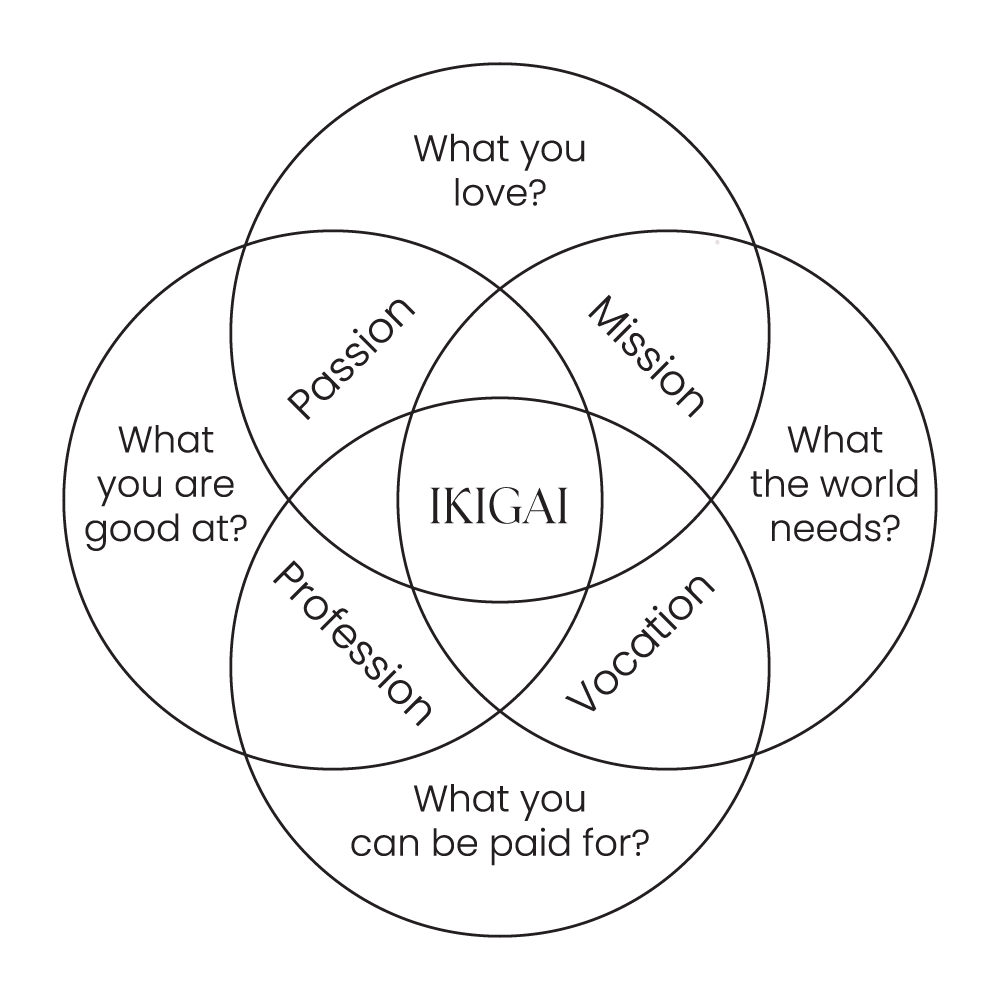

While many Westerners have first encountered ikigai online through a popular Venn diagram – showing overlapping circles of “what you love,” “what the world needs,” “what you can be paid for,” and “what you are good at” – this viral image both illuminates and oversimplifies the concept. The diagram, created by American entrepreneur Marc Winn and popularized by García and Miralles’ bestselling book, offers an accessible starting point for self-reflection, but this neat geometric representation risks reducing a nuanced Japanese cultural concept into a Western self-help or business motivational framework. The traditional understanding of ikigai encompasses subtle dimensions of duty, community, and spiritual fulfillment that often may not involve a “career path” at all. In an interview, author Ken Mogi has clarified that “even if you’re not paid for something you do, for example, if you love to paint a picture, and you’re not paid for that, that is ikigai, of course.” He goes on to explain that ikigai can be a pursuit that you may not even reach mastery in – like the desire to play guitar, even if you play it poorly – that counts as ikigai as well.

As we navigate an increasingly complex world, the wisdom of ikigai’s becomes globally relevant. Its emphasis on harmonizing individual fulfillment with social contribution offers valuable guidance for those seeking purpose in their lives. Whether expressed through a career path, an artistic pursuit, community service, or simply caring for one’s family, ikigai reminds us that true meaning often lies in the balance between personal satisfaction and service to others – a lesson as timely now as it was centuries ago.