At the exhibition “POKÉMON X KOGEI | Playful Encounters of Pokémon and Japanese Craft,” visitors discovered the dazzling spectrum of Japanese crafts and witnessed the creative spirit that keeps tradition fresh through the centuries. To dive deeper, we’re spotlighting five types of “kogei,” or Japanese craft, and a contemporary artist who is making each medium their own.

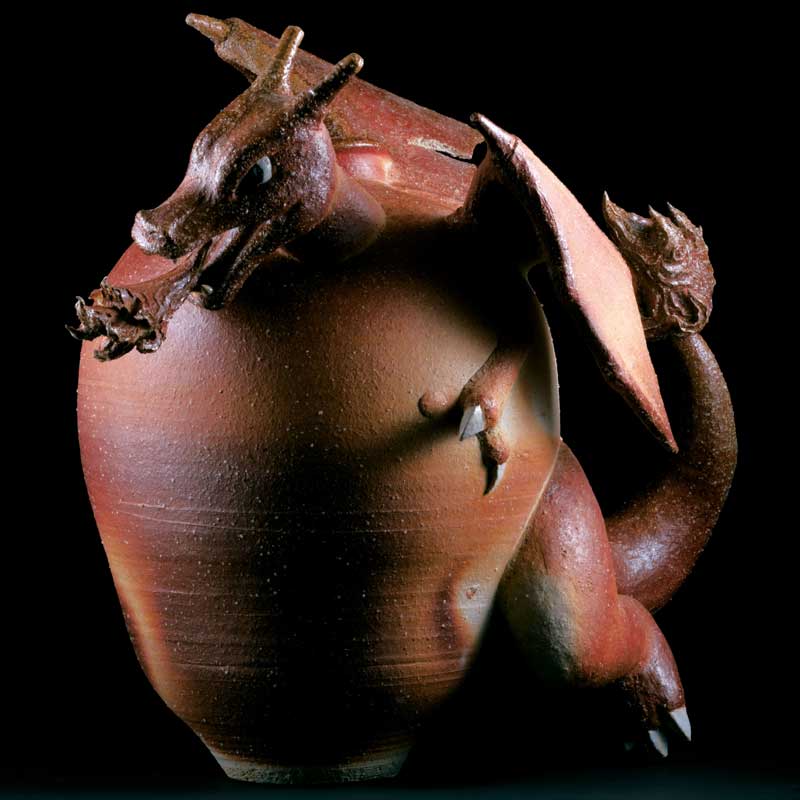

Ceramics (Shigaraki stoneware)

Near Kyoto and Nara, Shigaraki is famous as one of Japan’s “Six Ancient Kilns” where ceramics have been made for many centuries (to learn more about the history of ceramics in Japan, read more here). Its name came to denote a specific type of stoneware that local potters specialized in, made from a clay found in the area that's known for its high iron content and quartz particles. After the extraction and preparation of the clay, potters shape a vessel (either by potters’ wheel or by hand), then let it partially dry. Next, it is decorated, with simple incised details on the surface and fired in kilns often exceeding 1200 degrees Celsius, a process during which wood ash falls onto the vessel and creates a natural glaze. This technique has endured since the medieval period, evolving over time to produce not just storage jars, sake bottles, bowls and other household wares, but later tea ceremony vessels, flower vases and other items. Today, the Hyogo-born, Shigaraki-based artist Keiko Masumoto is putting her own spin on this tradition, injecting energy and humor into her creations. For her Shigaraki jars included in the exhibition, Matsumoto chose to work with “fiery” Pokémon like Moltres and Charizard, playfully reflecting the intrinsic connection between the element of “fire” and the art of pottery making.

Lacquer (Maki-e lacquer)

Similar to the transformations of Pokémon characters, Japanese lacquerware illustrates how to transform something volatile – a poisonous tree sap – into refined yet functional everyday objects like boxes, jars, trays, and more. While artisans in Japan began creating lacquerware as early as 7000 BCE in the Jomon period, it was in the Heian era (794-1185) that the more sophisticated maki-e developed. Maki-e literally means “sprinkled pictures,” and the technique involves creating intricate designs by sprinkling powdered gold and other metals on black lacquer surfaces, then adding a final coat of lacquer and and polishing the surface to produce a luminous effect. There are three main types of maki-e, including Togidashi maki-e, Hira maki-e, and Taka maki-e, which involve burnishing details and creating designs in relief. Maki-e can also be combined with other techniques like raden, to create even more stunning and intricate designs. Raden, also known as mother-of-pearl inlay, involves the use of thinly sliced pieces of iridescent shell to adorn the lacquer surface. The Tokyo-born Yoshiaki Taguchi is a second-generation metal artist who learned both maki-e and raden techniques from his father and carries on the family legacy in his surprising and bold creations. For this exhibition, Taguchi’s works include a black-lacquered jar where aluminum powder and oyster shell are used to depict a whirlpool on which Horsea rides and transforms, as well as a moody, jet-black tea caddy featuring a Moltres in full flame.

Metalwork (Menuki sword fittings)

The history of metalwork in Japan is deeply rooted in the craftsmanship associated with samurai culture. One remarkable tradition is the creation of decorative fittings, such as menuki, which adorned the handles of samurai swords, and served both a functional and aesthetic purpose. After the rise of the Tokugawa shogunate in the early 1600s, class hierarchies were rigidly enforced, with the warrior class at the top. Although the country was at peace, the samurai still wore swords as symbols of their status and often went to great expense to decorate their various parts. Menuki are metal ornaments that are woven under the wrappings (called tsuka-ito) on the sword’s hilt or handle. Their original function was to cover the pins that connected the grip to the sword’s iron blade itself, but over time they became mostly aesthetic. Common motifs of menuki include plants, insects, animals, and geometric patterns, and are typically made of brass in raised relief. They are usually coordinated with other decorative elements of the sword, including sword guards, sashes, and engraving on the blade itself. When the samurai era ended in 1868, many of these artists had to find other applications for their skills, so created ritual items, household goods, fashion accessories, jewelry, and more. Morihito Katsura hails from a family of such metal artists dating back to 1600’s Edo (present-day Tokyo), and he directly learned from his father Moriyuki Katsura, who specialized in metal fittings for swords. In 2008, Katsura was designated a Living National Treasure for his practice of chokin, or metal engraving, and his inventive work in a variety of styles has been honored worldwide. For this exhibition, Katsura created metal items riffing on the strength and boldness of creatures from the Pokémon universe, such as Umbreon-inspired menuki clasps in surprising colors.

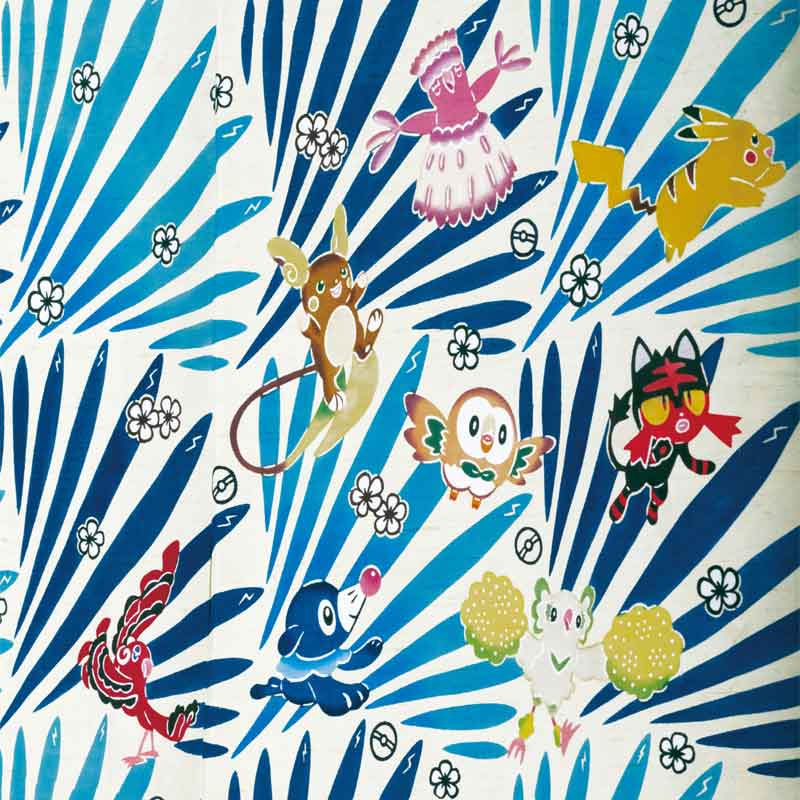

Textiles (Bingata)

Representing the geographical and cultural diversity of Japan, the brightly dyed textile known as bingata brings a vibrant island energy wherever it travels. With its roots tracing back to the Ryukyu Kingdom era (1429 to 1879), bingata holds deep cultural significance and has become a cherished symbol of Okinawan identity. This type of textile is produced by drawing and carefully cutting a stencil from mulberry paper, which is then applied to a piece of blank fabric (originally banana fiber cloth, but today more commonly cotton, linen, or silk). Common motifs include elements from nature like trees, leaves, and animals, as well as geometric designs. Once the design is placed on the fabric, artists skillfully apply dye by hand so that it only soaks through in certain areas, employing brushes or sponge-like tools to achieve precise and vibrant colors. This process can then be repeated to add other colors and layered patterns. After the dying is complete, the fabric is steamed and washed to let the color set. Historically, bingata was used to create kimono, which were worn across classes but with more vivid colors and bold patterns reserved for the royal family and nobility. The production of bingata was interrupted by World War II, but had a revival in the decades since, and in 1984 was designated an official traditional craft of Japan. Eiichi Shiroma is a 16th generation bingata artist, carrying on the practice his family has continued for over 600 years. The award-winning Shiroma is known for his faithfully traditional indigo dyeing techniques, as well as a flair for experimentation. Both traits are on display in his pieces for the exhibition (in separate rotations), including a bingata kimono that features Pikachu, Raichu, Rowlet, Liben, Popplio, and Oricorio, and connecting the craft’s island roots to the Pokémon island of Alola.

Woodworking (Hokkaido carving)

After Rain, 2022 | Toru Fukuda | Photo by Taku Saiki

After Rain, 2022 | Toru Fukuda | Photo by Taku Saiki

Northern Japan’s Hokkaido, with its abundant forests and rich cultural heritage, has long been a hub for woodworkers who skillfully transform blocks of timber into intricate works of art. The art of wood carving is part of the cultural heritage of the region’s indigenous Ainu people, who have long imbued their creations with symbolic and spiritual significance. Choosing from diverse trees, Hokkaido’s wood artists carefully select the appropriate wood, considering its grain, color, and durability, and use traditional tools such as chisels, gouges, and carving knives to bring their subjects to life. The deep connection to nature in Ainu culture is evident in their carvings, which often depict animals, mythical creatures, and ancestral spirits. Bears are an especially sacred creature, and are often represented through robust, energetic carving styles. Over time, woodcarving practices in Hokkaido have influenced and been influenced by techniques from the rest of Japan, including delicate inlaid woodwork (moku zogan), nailless wood joinery (sashimono), and more. The young artist Toru Fukuda was born and raised in Hokkaido and studied various types of woodcraft to hone his unique style. Working with over 100 types of wood, Fukuda creates sculptures that combine inlaid woodwork, curved surfaces, delicate cut-outs and surprising colors, forming 3-D scenes of animals, plant-life, and stunning visual effects (and have often gone viral on social media). For the exhibition, he crafted witty, self-contained scenes including a Pokémon Ho-Oh soaring into the sky, as well as a delicate Beautifly diorama – and never before have “still lives” been so “action-packed.”

Related Exhibition

Top: ©2023 Pokémon. ©1995-2023 Nintendo/Creatures Inc./GAME FREAK inc.

Bottom: ©JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles

Dates

07.25.2023 (Tue.) – 01.07.2024 (Sun.)

Location

JAPAN HOUSE Gallery, Level 2

Fee

Free

Exhibition-Related Programs

Talk 1 | Exploring Pokémon in Japanese Craft

Date

09.12.2023 (Tue.)

Time

05:00 PM - 06:15 PM (PDT)

This first installment of this webinar series invited two artists whose work is notable for the deft and detailed manner in which they explored the form and appearance of Pokémon through their craft techniques.

Photos by Taku Saiki, Left: Charizard/Shigaraki Jar, 2022, Keiko Masumoto | Right: Flying, 2022, Toru Fukuda

Talk 2 | POKÉMON X KOGEI Artistic Journey

Date

10.11.2023 (Wed.)

Time

05:00 PM - 06:15 PM (PDT)

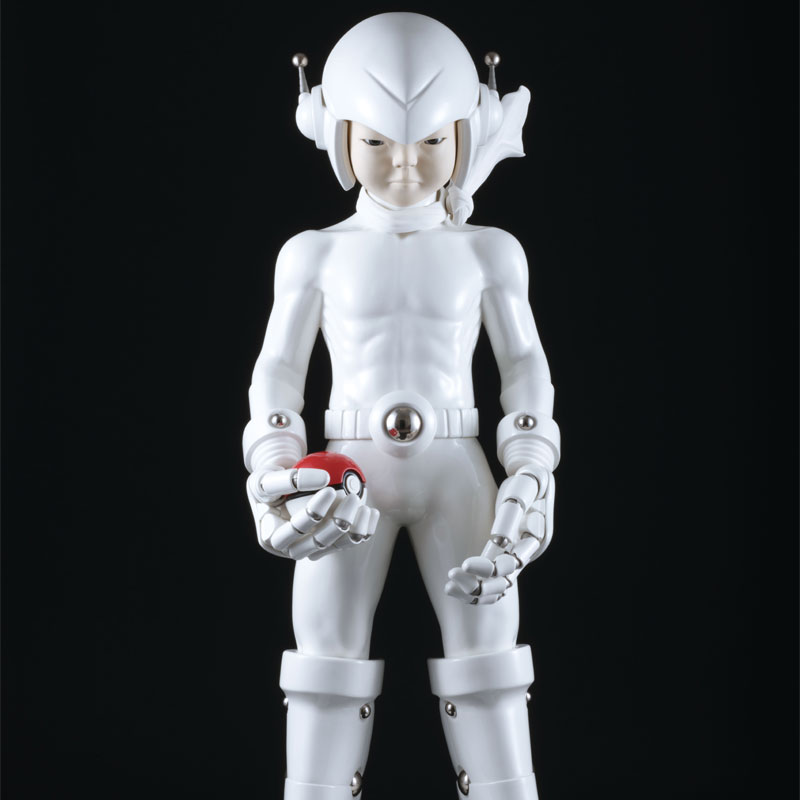

This webinar featured two artists whose innovative assimilation of science and technology delivered incredible results in their craft interpretation of Pokémon.

Photos by Taku Saiki, Left: Eevee (Left) and Jolteon (Right), 2022, Taiichiro Yoshida | Right: Tea Caddy, Electric Exchange Design (Right), Tea caddy, Unown Design, Black Granite Style (Back), Poké Ball Box (Front), Ornamental Box, "Mewtwo," Luminous Design, Raden Inlay (Left), 2022, Terumasa Ikeda

Talk 3 | Pokémon and Japanese Craftsmanship

Date

11.15.2023 (Wed.)

Time

05:00 PM - 06:15 PM (PST)

In this final webinar, viewers saw these artists’ creative processes and techniques, as well as the movement and internal structures of their creations in ways that are not visible in the exhibition display.

Photos by Taku Saiki, Left: Articulated Gyarados, 2022, Haruo Mitsuta | Right: Transformable Ornament, Rookidee/Corviknight, 2022, Yuki Tsuboshima

Media Sponsors

Promotional Partners

Shaymin with Fern Arabesque Pattern, 2022 | Kasumi Ueba | Photo by Taku Saiki

Shaymin with Fern Arabesque Pattern, 2022 | Kasumi Ueba | Photo by Taku Saiki Charizard/Shigaraki Jar, 2022 | Keiko Masumoto | Photo by Taku Saiki

Charizard/Shigaraki Jar, 2022 | Keiko Masumoto | Photo by Taku Saiki Venusaur, 2022 | Sadamasa Imai | Photo by Taku Saiki

Venusaur, 2022 | Sadamasa Imai | Photo by Taku Saiki “Moonlight” Pokémon Edition (Detail), 2022 | Shigeki Hayashi | Photo by Taku Saiki

“Moonlight” Pokémon Edition (Detail), 2022 | Shigeki Hayashi | Photo by Taku Saiki Cups (Pikachu), 2023 | Takuro Kuwata | Photo by Taku Saiki

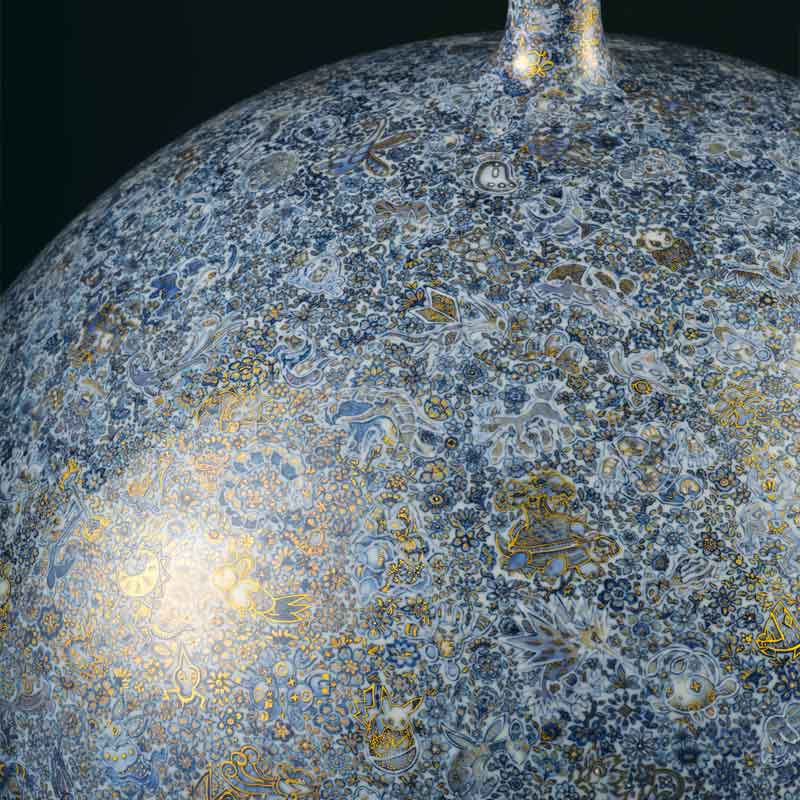

Cups (Pikachu), 2023 | Takuro Kuwata | Photo by Taku Saiki Vase with Pokémon of the Universe (Detail), 2022 | Yuki Hayama | Photo by Taku Saiki

Vase with Pokémon of the Universe (Detail), 2022 | Yuki Hayama | Photo by Taku Saiki Untitled, 2022 | Nobuyuki Tanaka | Photo by Taku Saiki

Untitled, 2022 | Nobuyuki Tanaka | Photo by Taku Saiki Tea Caddy, Electric Exchange Design, 2022 | Terumasa Ikeda | Photo by Taku Saiki

Tea Caddy, Electric Exchange Design, 2022 | Terumasa Ikeda | Photo by Taku Saiki Tea Caddy, “Call Spring,” Maki-e, 2022 | Yoshiaki Taguchi | Photo by Taku Saiki

Tea Caddy, “Call Spring,” Maki-e, 2022 | Yoshiaki Taguchi | Photo by Taku Saiki Articulated Gyarados, 2022 | Haruo Mitsuta | Photo by Taku Saiki

Articulated Gyarados, 2022 | Haruo Mitsuta | Photo by Taku Saiki Sash Clasp in Umbreon Shape, “Intimidating” (Top), Brooch in Umbreon Shape, “Sleep” (Center), Sash Clasp in Umbreon Shape, “Standing” (Bottom), 2022 | Morihito Katsura | Photo by Taku Saiki

Sash Clasp in Umbreon Shape, “Intimidating” (Top), Brooch in Umbreon Shape, “Sleep” (Center), Sash Clasp in Umbreon Shape, “Standing” (Bottom), 2022 | Morihito Katsura | Photo by Taku Saiki Eevee (Left) and Jolteon (Right), 2022 | Taiichiro Yoshida | Photo by Taku Saiki

Eevee (Left) and Jolteon (Right), 2022 | Taiichiro Yoshida | Photo by Taku Saiki Transformable Ornament, Rookidee/Corviknight, 2022 | Yuki Tsuboshima | Photo by Taku Saiki

Transformable Ornament, Rookidee/Corviknight, 2022 | Yuki Tsuboshima | Photo by Taku Saiki Kimono, “Island to Island,” Ryukyu Bingata, 2022 | Eiichi Shiroma | Photo by Taku Saiki

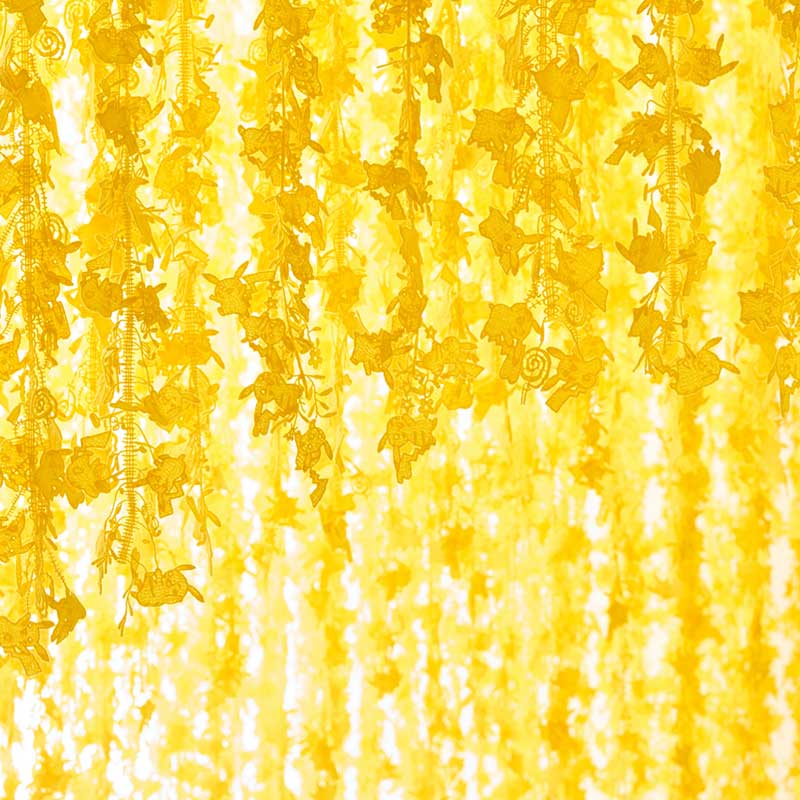

Kimono, “Island to Island,” Ryukyu Bingata, 2022 | Eiichi Shiroma | Photo by Taku Saiki Pikachu’s Adventures in a Forest (Installation Detail), 2022 | Reiko Sudo | Photo by Masayuki Hayashi

Pikachu’s Adventures in a Forest (Installation Detail), 2022 | Reiko Sudo | Photo by Masayuki Hayashi Kimono, “Herd,” Yuzen Dyeing, 2022 | Saori Mizuhashi | Photo by Taku Saiki

Kimono, “Herd,” Yuzen Dyeing, 2022 | Saori Mizuhashi | Photo by Taku Saiki Kimono Cloth, Edo Komon, “Gengar and Haunter,” 2022 | Yasuyoshi Komiya | Photo by Taku Saiki

Kimono Cloth, Edo Komon, “Gengar and Haunter,” 2022 | Yasuyoshi Komiya | Photo by Taku Saiki