While Japan’s wood craftsmanship is well known, there is another plant material that gives rise to just as much artistry: bamboo. Bamboo can grow to enormous heights and comprise entire “forests,” but technically bamboo is not a tree, but a member of the grass family. The plant is widespread across Asia, and over six hundred types of bamboo, or take, grow in Japan. For millennia, this ultra-versatile and sustainable material has occupied a special place in Japanese culture, used in everything from food to furniture. (Read about one of Japan's folktales, “The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter” or “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” here.) It also grows quickly, making it a highly renewable natural resource. As “sustainability” is increasingly central to the global design world, bamboo is back in the spotlight, providing the perfect chance to learn more about the artisans and techniques that make it both functional and beautiful.

Gourd-shaped Hexagonal-openwork Flower Basket

Gourd-shaped Hexagonal-openwork Flower Basket

by Tanabe Chikuunsai II

Photograph by Minamoto Tadayuki

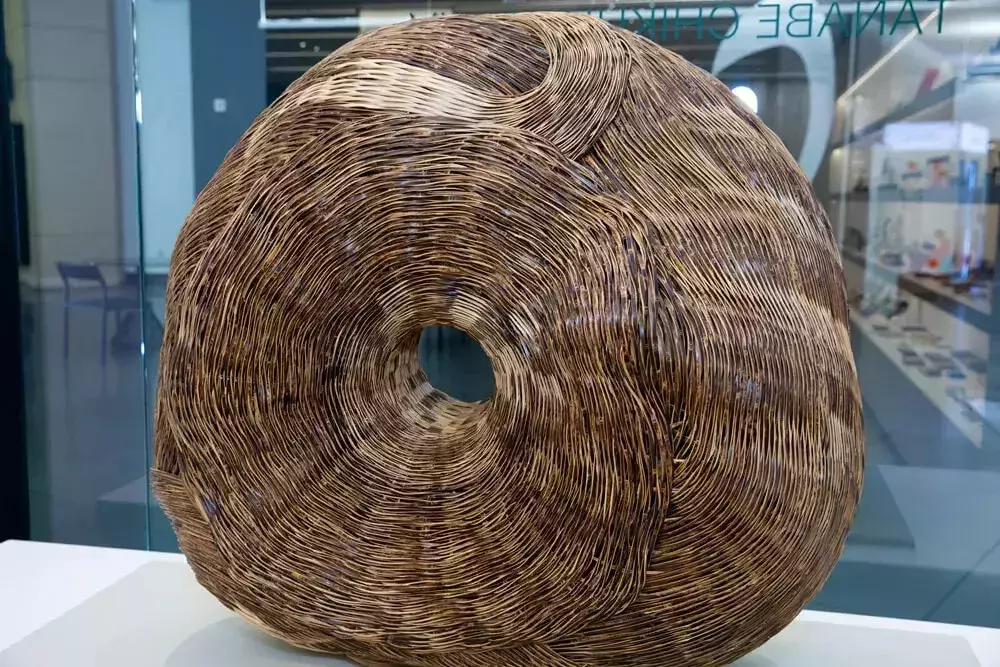

Creative City

Creative City

by Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Photograph by Minamoto Tadayuki

The term takezaiku, or “bamboo work,” refers to all kinds of bamboo craft, from architectural structures, to woven baskets, home products and refined art objects. In architecture, bamboo stalks have long been used alongside wooden timber and other materials, either for the actual building structure, or for design accents, or for the construction process itself (on building sites around the world, bamboo is still often used as temporary scaffolding). For smaller and more modular items like furniture, screens, or baskets, bamboo stalks are typically prepared by carefully cutting them and then splitting them into strips which can be woven into various forms and patterns.

Examples of bamboo basket-weaving in Japan have been found dating back to the Jomon period (about 10,000BC to 300BC), and many functional baskets were made for fishing, farming, storing and preparing food for the following centuries. However, as the tea ceremony gained prominence from the Muromachi period (1336-1573) onwards, baskets were made increasingly as decorative objects displayed in the home or in tea rooms. Baskets were prized accessories in the tea ceremony, particularly as vases for flower arrangements. From around the 15th century, many bamboo flower baskets were imported from China or created locally in the “Chinese style.” By the late 19th century, however, some Japanese bamboo basket makers began to specialize in bamboo flower baskets, varying materials and techniques to create a more native Japanese style. Using techniques such as “hexagonal” plaiting, “diamond twill” and “chrysanthemum base” styles, they created baskets with exquisitely detailed patterns and structural variations.

After WWII, plastic became cheap and widely available and replaced bamboo as a material for many everyday products, almost eradicating the need of bamboo objects and the artists who made them. However, in the 1960s and 1970s, conscious efforts of the Japanese government to protect this heritage saved bamboo crafts and elevated their status as well as that of their makers. In 1979, bamboo crafts from the Beppu region were first designated as “Traditional Arts and Crafts” (kogei), and today, eight regions of Japan are recognized as centers of bamboo-work, both for their preservation of traditional styles, as well as more their avant-garde approaches. In recent decades, the time and study required to become a skilled bamboo artisan has deterred many people from pursuing bamboo-work as a trade. Traditionally, aspiring artisans would apprentice for many years with a master to learn the trade, and typically, it would be passed down from one generation of a family to the next.

Photo by Minamoto Tadayuki

Photo by Minamoto Tadayuki

Today, many contemporary artisans are carrying on these family legacies, such as Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, the artist featured in JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles’ latest exhibition. Born in 1973 as Tanabe Takeo, he grew up surrounded by bamboo and after many years of study, inherited the name first bestowed on his great-grandfather, an important bamboo basket maker at the turn of the 20th century: Chikuunsai, meaning “Master of the Bamboo Clouds.” Chikuunsai IV’s work goes far beyond flower baskets and even small-scale woven bamboo sculptures, extending since 2011 to include large-scale installations at cultural spaces around the world. But his work still maintains its roots; each piece constructed through the painstaking preparation of bamboo strips, and the slow-earned knowledge of plaiting techniques and patterns.

Tanabe Chikuunsai I (right), Tanabe Kōunsai (center) and Tanabe Chikuunsai II (left) at Tanabe Chikuunsai I’s Solo Exhibition at the Mitsukoshi Department Store, Osaka

Newspaper unknown, July 1915

Photo courtesy of Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Tanabe Chikuunsai III (left), Tanabe Chikuunsai IV (right) and Elder Daughter

Photo courtesy of Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Through the work of today’s bamboo artisans, either part of a family lineage or passionate newcomers, new audiences are discovering the beauty and adaptability of bamboo as a material. In addition, this grass that can be woven into almost any shape and has strength comparable to steel also has the potential for for use in truly green design. While mastering bamboo-craft takes time, bamboo itself grows incredibly fast – some species can grow up to four feet a day, without pesticides or fertilizers, or even much water. It can yield 20 times more timber than a stand of trees in a similar-sized plot of land, and emit 30% more oxygen. Many are championing the role of bamboo for sustainability, including architects like Shigeru Ban, who are innovating new ways to use bamboo in larger-scale structures than ever before. As more designers look to inherently “green” traditions for the future of sustainable design, bamboo will be there, growing quickly and robustly, waiting to find new life in harmony with human creativity.

Note: Traditionally, the Japanese family name comes first, followed by personal name or artist name.

Related Exhibition

LIFE CYCLES | A Bamboo Exploration with Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Dates

07.28.2022 (Thu.) – 01.15.2023 (Sun.)

Location

JAPAN HOUSE Gallery, Level 2

Fee

Free